How to read a short story collection

(Tiny Camels / Jonathan Gibbs)

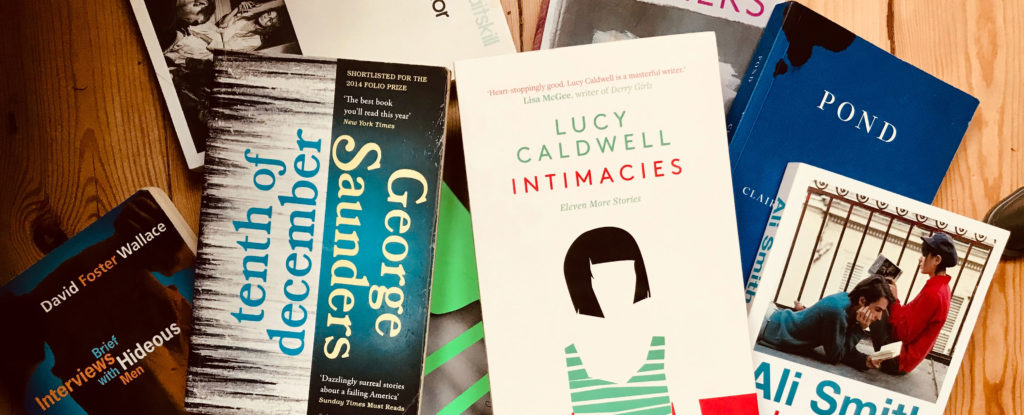

So Lucy Caldwell’s Intimacies was one of my May reads, but I’ve split off into a separate blog to write about it, because I found it so interesting. I’ll say straight out that it is a great collection of stories, which much of the same calm, wry, politically and socially observant writing as her debut collection, Multitudes, but the reason I want to write about it (and not just it) is something different from just the quality.

I’ll also say second out that I met Lucy last year, when she kindly agreed to talk with me, and Michael Hughes and David Collard, for the Irish Literary Society about my poem Spring Journal and its connection to Louis MacNeice, of whom she is a great fan, as evidenced by her Twitter handle @beingvarious, and in fact the great anthology of contemporary Irish short stories of the same title that she edited; and she was kind enough to say some words about the book, which were used for a blurb. So I am in her debt for that.

And but so…

Short story collections.

I own maybe 100 single-author individual collections, as opposed to anthologies or Collecteds, but I’ve got no idea how many of them I’ve read in their entirety. I do read plenty of short stories, not least because of A Personal Anthology, the short story project I curate, which pushes me weekly in all sorts of directions, some of them new, some of them old, but when I do read stories I mostly read one, two or at most three stories by a particular author at a time.

This partly comes down to the practicalities of reading. A short story you can read in the bath, and a long decadent bath with bubbles and candles might stretch to three or four, depending on the writer. Or, as I have done this afternoon, sitting outside in the garden, reading ‘Heaven’, the final story in Mary Gaitskill’s seminal Bad Behaviour, a story which… but now’s not the time.

But seriously: what a story!

What I generally don’t do is read collections in order, from start to finish. I appreciate that this might be annoying for authors, who presumably put some effort into sequencing their collections, but a collection isn’t like a music album – not quite – which lends itself almost exclusively to listening in order. (I remember when CD players came out, and the novelty of random play. It’s not something I would ever do now, and I find it annoying that it seems to be a default setting on Spotify.)

The reason why I don’t tend to read collections in order, is partly because I like reading stories in isolation. I think it’s a Good Idea. If – to be reductive about it – novels are a writer doing one big thing, slowly, and stories are writers doing a small thing, over and over, then there is a risk, in reading a collection in one go, of seeing a writer repeat themselves. After all, they most likely wrote the stories to be read individually. Read me here, doing my thing, in The New Yorker. Read me here, doing my thing again, in Granta. And here I am, doing something similar but different in The Paris Review.

Some collections of stories are just that: agglomerations of pieces that have individual lives of their own, published here and there, and their coming-together is primarily a commercial rather than an artistic act. Some collections are more integrated than that, more self-sufficient or autarchic, having no particular dependence on anything outside of its little biosphere.

As I tweeted about the theme of this blog, John Self mentioned David Vann’s Legend of a Suicide and Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son as two collections that operate like this, that need to be read in order. He’s right, though annoyingly I don’t have either to hand. The Vann I think is in a box in the loft, and I’ve never owned a copy of Jesus’ Son, despite it being a touchstone of sorts. Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond is another example, with its famous ambiguity as to whether it’s a novel or a collection of stories, but that has the oddity that I think you could read it in any order.

There must be others. I might think further and come back to this. You might have thoughts yourself.

So once you’ve leaned away from the idea of reading a collection in one go – to avoid the risk of diminishing marginal returns – then the need to read them in order seems somehow weaker. So that’s what I do. I take a collection down from the shelf, a new one or an old one, and I scan the contents page; I consider the titles; I look at the page-length. I make my choice.

Reading a book is all about giving your time to the writer, putting yourself in their power. Choosing to read a collection out of order is a way of taking back a small amount of that power, or control, or cocking a snook, in a minor way. You wouldn’t do it with a novel (unless you’re reading Hopscotch) but with a collection: what harm can it do?

Certainly I’d probably start with the opening story, or at least give it a chance to do its work on me. The opening story of a collection, no less than a title story – a story that the writer has chosen to stand for the collection as a whole – is a way of a writer setting out their stall. This is, broadly speaking, what I’m about in these stories. It makes sense to take them up on their offer.

But I’d be as likely to lump for one in the middle, with an intriguing title, or that seems the right length for the moment. The last story? Unlikely. Presumably the writer put a story last that think ended the collection well, so it’s worth bearing that in mind too. Every story has an ending, but stories can have many different kinds of endings, and the kind of ending they choose to end the whole collection is, like the ending of a novel, something particular, and potentially precious.

Not reading the stories in order doesn’t mean ignoring the order they come in. Even if you read a final story first, or penultimately, it makes a difference that you know it’s the last story in the book.

As an example, Chris Power’s debut collection Mothers is scaffolded by three linked stories, the first one, one in the middle and one at the end. You don’t have to read them in order, but once you’ve read them, you see how they gain power from their placing.

Lucy Caldwell’s Intimacies I think does need to be read in order.

Broadly speaking, the stories in it are about motherhood, and womanhood. Babies – unborn, lost, marvellously, exhaustingly there – haunt the book. Often the main characters are mothers, but in ‘Jars of Clay’ the narrator is a young American Christian woman come to Ireland ahead of the Repeal the 8th referendum to campaign for the no vote. The stories are all contemporary, with some memories floating in here and there, and the sense of the recent past of Ireland and Northern Ireland is ever-present.

(read the whole article at Tiny Camels / Jonathan Gibbs)