(chosen for Granta Magazine. See the original article here)

1. Dusty Bluebells documentary

The Northern Irish poet Stephen Connolly, @closeandslow, tweeted a link to this old BBC NI documentary from 1971, and I happened to see the tweet, watch the documentary, and was entranced. It’s about Belfast children and the street songs they sang, the games they played, even as their wider world was disintegrating around them. It took me right back to my childhood, the endless skipping games and cat’s cradles, but even more preciously, it sparked a story, ‘The Ally Ally O’, which is now the first story in my debut collection. (Stephen: if you happen to see this, the pints are on me.)

2. The Architecture Foundation: New Architects 3

Every ten years, the Architecture Foundation selects Britain’s best emerging practices and publishes the result in a glossy hardback. (Think Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists . . .) I’m very proud that my husband has made it in here with his new practice, Gatti Routh Rhodes. They’re currently designing a new church and community building opposite the V&A Museum of Childhood in east London.

In the unlovely grid of streets between Bethnal Green and Whitechapel, a stone’s throw from Brick Lane, is the magical Spitalfields City Farm, an oasis of wildflowers, bees, ponds, organic vegetables and a treehouse (not to mention the animals). I come here several times a week to buy fresh eggs and pick vegetables, and inspired by the City Farm, I’ve been trying to create a (miniature) wildlife haven on my inner-city balcony. As well as herbs I’m growing echinacea, lunaria annua, or honesty, devil’s-bit scabious, buddleia and achillea millefolium, which always makes me think of Paul Muldoon’s poem, ‘Yarrow’:

Achillea millefolium: with its bedraggled, feathery leaf

and pink (less red

than mauve) or off-white flower, its tight little knotof a head,

it’s like something keeping a secret

from itself, something on the tip of its own tongue.

4. Enda Bowe’s At Mirrored River

Irish photographer Enda Bowe won The Solas Prize this year with his series At Mirrored River, in which he visited the same, small, unnamed Irish town for four years, taking portraits of the town and its young people. More than just the beauty in the mundane, he captures his subjects at their most hopeful and most vulnerable, their dreams and fears shining from them. The series will be exhibited at Visual Carlow this July, and published as a book to coincide with the opening; the poet John Glenday and I have both contributed words for it.

Maybe it’s the chronic lack of sleep, maybe it’s the time of day, but it never fails to make me weepy: the moment when the stars in the sky turn into white flowers blossoming. In the Night Garden (on CBeebies every evening at 6.20 – but you either know that already or you don’t need to) has been a guilty pleasure of mine since my toddler started watching television. But! I came across an article by a Chaucer scholar who said it’s basically an introduction to the conventions of medieval poetry, and specifically early Chaucerian dream visions. Who knew! She quotes The Parliament of Fowls, The Legend of Good Women, The Book of the Duchess and more, and it’s a pretty darn convincing case.

From Belfast to London and back again the eleven stories that comprise Caldwell’s first collection explore the many facets of growing up – the pain and the heartache, the tenderness and the joy, the fleeting and the formative – or ‘the drunkenness of things being various’.

From Belfast to London and back again the eleven stories that comprise Caldwell’s first collection explore the many facets of growing up – the pain and the heartache, the tenderness and the joy, the fleeting and the formative – or ‘the drunkenness of things being various’.

Lucy Caldwell talks to Séan Rocks on RTE Radio about her debut collection of short stories “Multitudes”

Lucy Caldwell talks to Séan Rocks on RTE Radio about her debut collection of short stories “Multitudes” Were you always going to be a writer?

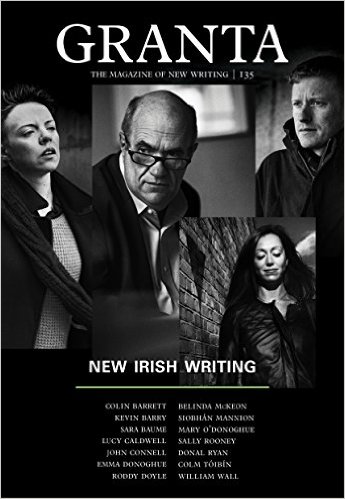

Were you always going to be a writer? Granta 135 is a snapshot of contemporary Ireland, which shows where one of the world’s most distinguished and independent literary traditions is today. Here international stars rub shoulders with a new generation of talent from a country which keeps producing exceptional writers.

Granta 135 is a snapshot of contemporary Ireland, which shows where one of the world’s most distinguished and independent literary traditions is today. Here international stars rub shoulders with a new generation of talent from a country which keeps producing exceptional writers.